Airway Devices 💨

Airway devices facilitate controlled delivery of oxygen and anaesthetic agents to the patient’s lungs. These are the ones you should know for your exam…

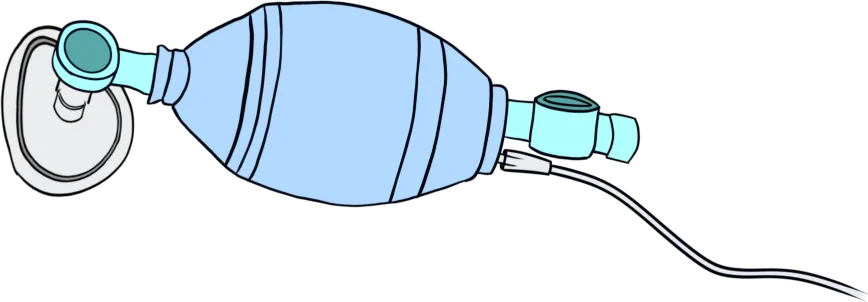

Bag Valve Mask

A bag valve mask (“BVM” for short) has three important parts…

- A mask with a cuff that (ideally) forms an airtight seal around the patient’s mouth and nose

- A self-inflating bag attached to the mask

- Valves that route air from the bag into the mask and stops the patient from breathing back into the bag

A BVM, coupled with good positioning, lets us non-invasively ventilate patients that have lost their respiratory drive and airway reflexes.

Knowing how to “bag” a patient is a life-saving skill.

Airway Adjuncts

Unconscious patients lose their airway tone, which makes it tricky to use the BVM. A combination of head tilt, chin lift and jaw thrust usually lets us open them up again.

When positioning doesn’t work, we use adjuncts to bypass the obstruction.

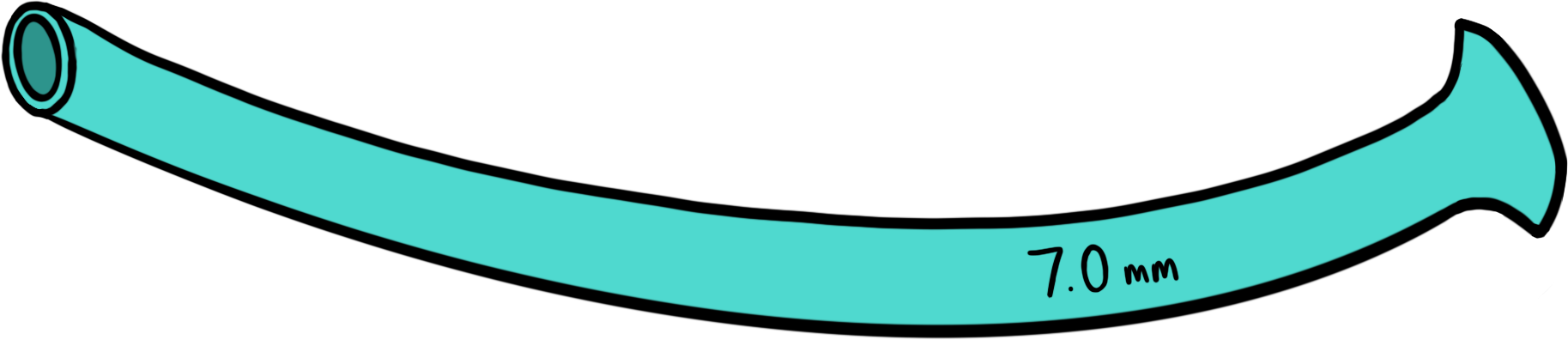

An oropharyngeal airway (often called a Guedel) is a curved, rigid tube inserted into the mouth. It creates a clear passage to the pharynx by passing between the tongue and palate.

Instead of a Guedel, you can use a nasopharyngeal airway: a short, lubricated rubber tube inserted through the nose until it reaches the nasopharynx.

Unlike a Guedel, a conscious patient can tolerate a nasopharyngeal airway.

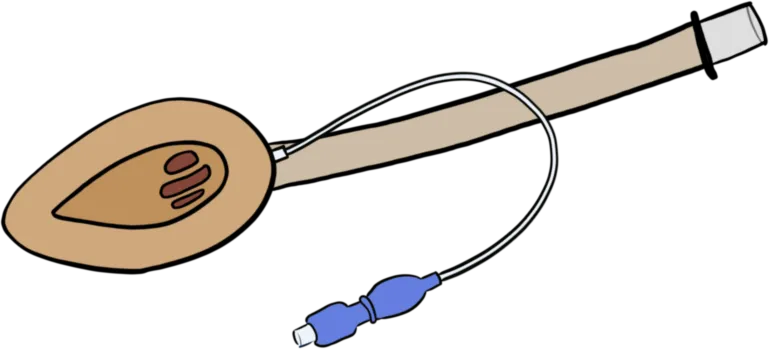

Laryngeal Mask Airway

A laryngeal mask airway (“LMA” for short) covers the larynx at its opening and creates a seal with an inflatable cuff. LMAs are safe, easy to use, and used for the majority of patients needing short-term ventilation.

An LMA isn’t suitable for critically unwell patients and for operations that require high ventilator pressures (e.g. laparoscopy) or surgical access to the airway (e.g. tonsillectomy).

Endotracheal Tube

An endotracheal tube (“ETT” for short) is a flexible plastic tube with an inflatable cuff that forms an airtight seal inside the trachea. Anaesthetists guide the tube through the mouth and between the vocal cords using a laryngoscope.

A patient with an ETT is “intubated” and this is the most secure of the airway devices. They’re also the riskiest to put in because patients must be deeply sedated and paralysed to tolerate intubation. For difficult cases, a thin flexible rod called a Bougie (say “boo-jee”) can help guide an ETT into the trachea.

Laryngoscope

The shape of the human jaw and the position of the larynx in the throat make it almost impossible to insert an ETT blind. We use special positioning and a laryngoscope to align the mouth, pharynx and larynx to directly visualise the vocal cords.1

There are different shapes of laryngoscope for different airways. Most adults will suit a Macintosh blade. Many theatres have a video laryngoscope that can see around corners and show you a magnified view of the airway.

Yankauer Sucker

Suction is vital for clearing the airway and preventing aspiration. A Yankauer sucker is a curved rigid tube with a bulbous tip that prevents incidental damage.

The Anaesthetic Machine 📺

The anaesthetic machine mixes gasses (oxygen and nitrous oxide) and passes them through a vaporiser filled with a volatile anaesthetic agent (e.g. sevoflurane), which is then delivered to the patient through a ventilator.

The machine has all the monitoring equipment needed to give a safe anaesthetic. There are dozens of safety and backup systems that keep it running even when disconnected from electricity and gas supplies.

Circle Breathing System

The anaesthetic machine uses a circle breathing system to minimise wastage of anaesthetic gasses because they are expensive and bad for the environment.2

Air in the circuit is delivered to the patient automatically by a ventilator. The exhaled air is returned to the circuit where CO2 is removed using a soda lime scrubber that converts the CO2 into calcium carbonate.

Air only moves in one direction through the circuit thanks to a series of one-way valves. The circuit is continuously topped up with a slow trickle of gas and anaesthetic agent (“fresh gas flow”) to make up for leaks and the volume of the CO2 removed by the scrubber.

Monitors 👀

The monitors help us follow a patient’s vital physiology so that we can identify and treat problems as we go.

Oxygenation

The pulse oximeter allows non-invasive measurement of blood oxygenation using coloured light. We sometimes supplement its readings with serial arterial blood gas samples in major surgery.

Blood Pressure

An automatic sphygmomanometer (“cuff”) that cycles every few minutes is fine for most cases. For critically unwell patients, blood pressure can be measured from an arterial line to get second-to-second monitoring.

Temperature

Patients get cold during surgery because they are laying still in an air-conditioned room with their clothes off. Operative hypothermia causes postoperative badness, so we actively warm patients to prevent it.

You’ll often see a disposable hot air blanket (brand name “Bair Hugger”) used for this purpose. You might also see fluid warmer when large intravenous infusions are needed.

Gas Analysis

Anaesthetic machines continuously analyse air from the breathing circuit to calculate the concentrations of O2, CO2, and inhaled anaesthetic agents.

The concentration of a gas at the end of expiration approximates its concentration in the alveoli (its end-tidal concentration). Since alveolar gases equilibrate with arterial gases, end-tidal concentration can be used to estimate the amount of gases in arterial blood.

BIS

The Bispectral Index Monitoring System (BIS) is intended to be a dimensionless measure of anaesthetic depth derived from spectral analysis of a frontal electroencephalogram (the little stickers on the patient’s forehead).

Neuromuscular Monitoring

We often paralyse patients under anaesthesia, and we monitor depth of muscle relaxation with a nerve stimulator.

The most common system stimulates the ulnar nerve with a train of four3 twitches (TOF) applied via the forearm. The resulting contractions in adductor pollicis are measured with an accelerometer or strain gauge.

The number of conducted twitches is the TOF count. When all four twitches are present, the computer compares the magnitude of the first and final twitches with the TOF ratio.

When the TOF count is zero, the patient is fully paralysed. When the TOF count is four and the TOF ratio is greater than 0.9, the patient is fully reversed.

Lines 🩸

Peripheral Intravenous Cannula

Needs no introduction. Take this chance to practice putting them in.

Central Line

A multi-lumen line that goes in the internal jugular, femoral, or subclavian vein. They’re ideal for vasopressors and highly irritant medications.

Arterial Line

A cannula inserted into the radial or ulnar artery that can be used for blood pressure monitoring and repeat sampling of arterial blood.

We never use them for drug administration.

Intraosseous Line

In rare cases where timely intravenous access is impossible, we drill into bone and infuse medications there instead. You can push fluid at about the same rate as an 18G (green) intravenous cannula.

Line Warmer

Patients get cold during surgery. Large infusions further reduce core body temperature, so we sometimes heat them up using an electric line warmer.

Emergency Equipment 🚨

Emergency Bell

This button is the most important piece of emergency equipment equipment in a theatre. Your approach to every emergency should start with calling for help.

Airway Trolley

The airway trolley is used in every routine intubation but it also contains the equipment needed in an airway crisis. There is one drawer for each approach: BVM, LMA, and ETT. The bottom drawer is always the CICO kit.

Dantrolene

Somewhere in the building, there is a large supply of dantrolene. It’s the only drug that treats malignant hypertheramia, one of the rarest anaesthetic emergencies.

There is some disagreement about how best to conceptualise the process of laryngoscopy. Life in the Fast Lane has a good summary. ↩

Prasanna Tilakaratna’s “How Equipment Works” has an excellent exploration of circle breathing systems. ↩

We can used other nerve-muscle combinations and different stimulation patterns to examine very deep levels of block. Life in the Fast Lane’s ‘Part One’ notes provide a good overview ↩