Perioperative Medicine 🩺

Every hospital has a perioperative clinic where high-risk patients are seen by anaesthetists before their operation. You’ll be there for a session or two.

Perioperative medicine encompasses every stage of the surgical journey. Our thinking has changed a lot recently, so I’d like to introduce you to Grocott and colleagues’ excellent treatise on managing surgical candidates…

The Old Model

In the bad old days, patients needing non-urgent surgery would be identified as surgical candidates and allocated a theatre date. High-risk patients might be referred to a pre-anaesthetic clinic before the operation.

In the available time, anaesthetists would investigate and optimise comorbidities as much as possible. Cases were often delayed or cancelled at short notice when unexpected risks were identified too late.

Vulnerable patients received surgery before they were optimised and frequent delays led to wasted resources and much consternation.

The New Model

Patients needing surgery are identified during the contemplative phase and risk-stratified using simple screening tools. High-risk patients are discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting of surgeons, anaesthetists and allied health staff.

Medium and low-risk patients go to surgery school, a multidisciplinary “pre-habilitation” program with pre-defined “add-on” treatments for problems like…

- Weight loss

- Smoking cessation

- Anaemia management

- Cardiorespiratory fitness

- Psychological preparation

Successful patients progress to a final pre-anaesthetic check and are booked for timely surgery. This approach promotes sound decision-making and gives patients the best chance of a successful operation.

Taking an Anaesthetic History 🗣

Anaesthetic history-taking is an elaboration on standard history-taking with a special interest in risk factors for anaesthetic complications.

Here are the basics…

- Introduction

- Identity

- Demographics

- Operation

- PMHx

- Cardiac

- Respiratory

- Gastrointestinal

- Renal

- CNS

- Chronic pain

- Everything else

- Allergies

- Regular medications

- Opioid utilisation

- Past anaesthetic history

- Type of anaesthetic

- Complications

- Airway issues

- Family anaesthetic history

- Malignant hyperthermia

- Pseudocholinesterase deficiency

- Social history

- Smoking

- Alcohol

- Substance use

- Exercise tolerance (METs)

Relaying Comorbidities

For each active disease, anaesthetists want to know the ⭐️ STARS ⭐️

- Severity

- Treatment

- Aftermath (complications)

- Risk factors

- Stability

Anaesthetic history-taking is almost never done independently by junior doctors but it remains a surprisingly popular OSCE station.

Examination 🩺

The majority of anaesthetic examination is a rehash of what you already know: heart, lungs and end-of-the-bed-o-gram.

- General inspection

- Walking fitness

- Work of breathing

- BMI

- Medical aids

- Vein quality

- Cardiovascular

- Respiratory

The new part is airway examination, which helps to predict difficult airways in the hope of avoiding a disaster.

- Airway inspection

- Neck circumference (larger is worse)

- Neck length (shorter is worse)

- Surgical or radiotherapy scars (stiff or altered anatomy)

- Neck tests

- Atlanto-occipital range of motion (difficult to assess)

- Thyromental distance (ideally at least 6 cm)

- Jaw tests

- Opening (ideally at least 4cm between incisors)

- Dentition (missing teeth bad for bagging, loose teeth bad for intubating)

- Jaw protrusion (ideally bottom incisors can protrude past top incisors)

- Mallampati score

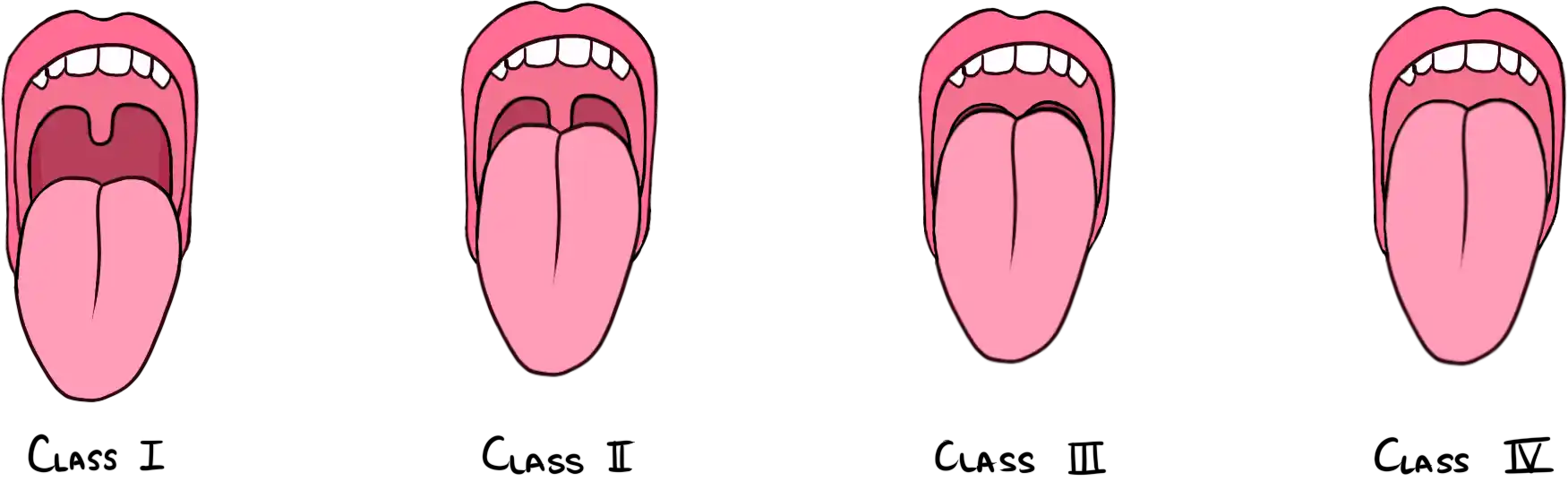

Mallampati Score

The Mallampati score aims to predict difficult airways based on the appearance of the oropharynx when a patient is awake. Higher is worse.

It is a poor stand-alone test for difficult intubation, but we do it anyway. Lundstrøm et al. (2011) found that a Mallampati score of III-IV only had a sensitivity of 35% for detecting difficult airways. Yikes.

Fitness for Surgery 💪

The American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification (“ASA” for short) is a quick way to describe a patient’s fitness for surgery. The six classes are:

| ASA | Definition | Vignette |

|---|---|---|

| I | A normal healthy patient | Healthy, non-smoking, fit patient |

| II | A patient with mild systemic disease | BMI 30-40, smoking, perhaps a well-controlled “lifestyle” disease with no functional impact |

| III | A patient with severe systemic disease | BMI > 40, severe functional limitation from poorly-controlled disease |

| IV | A patient with severe disease that is a constant threat to life | Currently failing organs (heart, lungs, kidneys) but doesn't need this surgery to survive |

| V | A moribund patient who would not survive without surgery | |

| VI | A brain-dead patient who is an organ donor | |

They don’t technically predict anaesthetic risk but they give you the gist. They are worth memorising because they make for a great exam question.

Exercise Tolerance

The preferred measure of perioperative aerobic fitness is the metabolic equivalent (MET). One MET is equal to a V’O2 of 3.5 mL/kg/min (the resting V’O2 of a healthy 40 year old 70 kg male).

A patient is considered “fit” when they can achieve four METs, which is roughly equivalent to walking up a flight of stairs (without stopping) or walking one kilometre on flat ground.

Informed Consent 📝

Consenting patients for a procedure is a core skill for junior doctors. Consider using the excellent PRBRA structure…

- Procedure

- Before

- During

- After

- Rationale

- Benefits

- Risks

- Common

- Rare

- Life-threatening

- Alternatives

The nature, rationale and benefits of anaesthesia are easy to work out. The risks are less obvious, so here are some to know for your exam…

- Common

- Sore throat

- Drowsiness

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Rare

- Dental injury

- Emergence delirium

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Awareness1

- Life-threatening

- Anaphylaxis

- Death

Fasting 🍔

Eight hours for solids and two hours for clear fluids.

We fast patients before surgery so they don’t aspirate during induction.

Patients are much more worried about this than anything else. ↩