The Aim of the Game 🧠

The purpose of general anaesthesia is to induce a reversible loss of consciousness with amnesia, analgesia and some degree of muscle relaxation.

Getting Ready 📝

It’s finally time to get your patient off to sleep. Induction feels like a flurry of activity, but if you watch closely you’ll observe the following common elements.

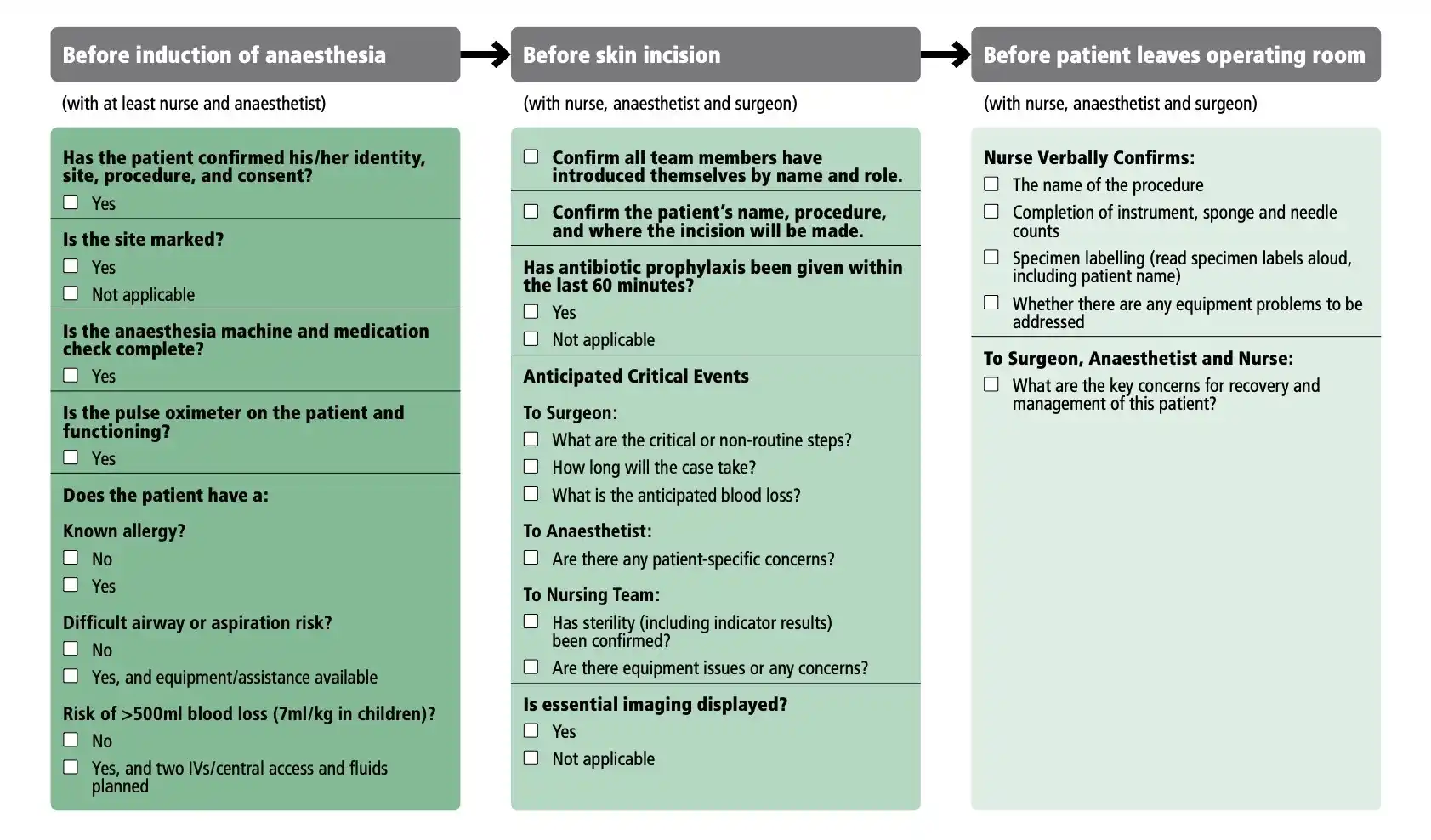

Team Time Out

Before a patient goes to sleep, the whole team does a surgical safety checklist. All hospitals around the world use a version of the WHO standard to confirm they have the right patient for the right operation and that everyone is ready to proceed.

Monitoring

It’s time to attach all of the gadgets and gizmos that our anaesthetic technician prepared between cases.

IV Access

If it’s not done already, the anaesthetist will insert an IV cannula while the technician in attaching the monitors. Now’s your chance to get some cannula practice done under expert supervision.

If you’re doing the cannula, ask which hand to put it in. Sometimes lines become inaccessible once the patient is positioned for surgery.

Pre-medication

Before induction, anaesthetists will pre-medicate with a handful of agents…

- Sedatives to relieve anxiety and reduce the dose of induction agent

- Antibiotics for prophylaxis against surgical infections

- Opioids to blunt the airway reflexes (they take a while to work)

Pre-oxygenation

After induction, patients will have a period of apnoea. To extend the safe apnoeic time, we pre-oxygenate patients with 100% O2 to replace the nitrogen-rich air in their lungs.

Once apnoeic, that extra oxygen continues to diffuse across the alveolar membrane and maintains oxygenation for about four times longer than normal air.

A patient is sufficiently pre-oxygenated when the expired concentration of oxygen is greater than 80% (i.e. FetO2 ≥ 0.8).

Induction 🛫

Hypnosis

Now we give an induction agent to render the patient unconscious. Propofol is nearly ubiquitous for this task, but you might see alternatives like sodium thiopentone and ketamine. Patients are usually unconscious in 30 seconds.

Paralysis

We paralyse to facilitate intubation and when the surgery requires it. It’s vitally important to paralyse patients after they’ve fallen asleep to avoid awareness: the experience of being awake but unable to move (or breathe).

There are four muscle relaxants routinely used in Australia:

| Drug | Dose | Onset | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suxamethonium | 1 mg/kg | 30 s | 10 m |

| Rocuronium | 0.6 mg/kg | 90 s | 30 m |

| Vecuronium | 0.1 mg/kg | 3 min | 30 min |

| Cisatracurium | 0.15 mg/kg | 30 s | 40 min |

Know the names for your exam but don’t bother memorising the doses.

Getting an Airway 🦷

We initially ventilate patients with a bag valve mask to maintain oxygenation and to make sure we can deliver oxygen if airway instrumentation fails.

How to Bag A Patient

Bagging is easy to describe and hard to do. This is your time to practice.

Nail Your Posture

Relax your shoulders, avoid craning your neck (it never helps) and use your big arm muscles to hold position. Your arms will really hurt after a few minutes.

Utilise Positioning

Move the table so the patient’s head is at the level of your elbows. Put their head in the “sniffing the morning air” position: head back, chin up, and jaw forward.

Get a Grip

Hold the inlet of the mask in a pincer grip so that your thumb and forefinger make a letter “C” shape. Use the rest of your fingers the grip the mandible so that they make a capital letter “E” shape. Tuck your pinky finger behind the angle of the mandible to make it easier to lift.

If you push the mask down to make a seal, you will obstruct the patient’s airway. Instead, pull the patient’s jaw into the mask using your latter three fingers

Delegate

Use both hands to hold the mask while you’re learning. Once you’re comfortable (and your arm muscles are suitably huge), try holding the mask one-handed.

How to Insert an LMA

Open the patient’s mouth, slide the LMA past the tongue (the hardest part), and push gently until you feel some resistance. Always secure the LMA in place.

Don’t wiggle it around once it’s in. You might trigger laryngospasm.

How to Intubate

It’s harder than it looks! You are not expected to do this independently as a junior doctor, but here’s an overview of intubation with a Macintosh laryngoscope…

- Insert the laryngoscope in the right side of the mouth

- Sweep the tongue to the left and advance the blade so the tip sits in the vallecula (where the tongue meets the epiglottis)

- You then use the blade to lift the jaw, tongue and epiglottis upwards

- Gently insert the deflated tube between the vocal cords

- Advance the tube until the vocal cords are between the pre-marked guide lines

- Inflate the cuff and check your placement before securing the tube with tape

Never tilt the blade against a patient’s teeth. They will break off.

Intubation takes an afternoon to learn and years to master. For more details, check out Dr Chistine Whitten’s excellent blog: The Airway Jedi.

How to Check Your Work

Use these four tests to check that your airway device is working…

- See the chest rise when you ventilate

- Hear air entry in both lung bases

- See a convincing capnograph

- See mist in the endotracheal tube during exhalation

Any one of these can let you down, so check them all.

Troubleshooting 🎯

Anaesthetic medications are blunt instruments with a lot of common side-effects. These are the non-emergency problems that you’ll see a lot in theatre…

Induction Hypotension

Almost all induction agents cause a degree of hypotension through negative inotropy and vasodilation. We accept a degree of hypotension in healthy patients who are lying flat, but hypotension can be life-threatening in certain situations…

- Impaired cerebral auto-regulation

- Patients who are sitting up

- Severe coronary artery disease

The solution to hypotension should be tailored to the cause:

- Bleeding needs blood transfusion

- Dehydration needs fluid replacement (usually crystalloid)

- Vasodilation needs vasopressors (often metaraminol)

- Vagal stimulation needs anti-cholinergic agents

- Heart failure needs inotropes

- Bradycardia needs chronotropes

Bradycardia

Hypotension with bradycardia is usually related to an oversized discharge of acetylcholine from the parasympathetic nervous system. Surgery of the abdomen and cervix are especially likely to trigger such a discharge.

The solution is to give atropine or glycopyrrolate, which antagonise the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor.

Bronchospasm

Bronchospasm under anaesthesia is relatively common and is managed in much the same way as in the awake patient:

- Give inhaled bronchodilators (there’s an adapter for puffers)

- Salbutamol

- Terbutaline

- Ipratropium

- If inhaled therapy isn’t working, switch to IV therapy

- Aminophylline

- MgSO4

- Ketamine1

Never treat wheeze without paying mind to its trigger. Common culprits are volatile agents, anaphylaxis, and asthma. Kids with respiratory infections are famously able to bronchospasm with minimal provocation.

The only thing ketamine doesn’t work for is ketamine overdose. ↩