Managing an Emergency 😱

Modern anaesthesia is very safe. You’re unlikely to come across a true anaesthetic emergency during your placement. Instead, you need to know these three things for your exams…

- How to approach a critically unwell patient

- How to manage a patient in cardiac arrest

- How to recognise and treat anaphylaxis

Approaching Sick Patients

You will inevitably be the first responder to a deteriorating patient. A structured approach saves time and stops you from missing anything important.

- Always check for danger

- Check if the patient is responsive

- When unresponsive, check for a pulse and breathing then start CPR when you don’t find them

- When responsive, keep calm and carry on

- Send for help

- In an exam, you will always need to send for help

- Airway

- Patent?

- Protected?

- Apply 15L O2 via a non-rebreather mask

- Breathing

- Respiratory rate

- Auscultate the chest

- Tracheal deviation

- Effort of breathing

- SpO2

- Circulation

- Radial pulse

- IV access

- Blood pressure

- Central capillary refill

- ECG (rhythm strip)

- Urine output

- Disability

- Pupilary responses

- Dextrose (blood sugar level)

- Documentation

- Drug chart

- Exposure

- Systematically look at every part of the patient

- Preserve their dignity while doing so

Repeating the entire Advanced Life Support curriculum is beyond the scope of the Survival Guide. Instead, focus on your structure and practice for the OSCE.

Anaphylaxis 🐝

Anaphylaxis is an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction characterised by massive histamine release from mast cells. It causes life-threatening distributive shock and airway oedema, plus gastrointestinal upset and rash in some patients.

Anaesthetic agents cause a lot of anaphylaxis. The main culprits are muscle relaxants, sugammadex and antibiotics. Sleeping patients can’t tell you that they feel sick, so constant vigilance is required. Keep a look out for…

- Unexplained hypotension and tachycardia

- Rising ventilator pressures

- A rash (rarely witnessed)

- Bronchospasm

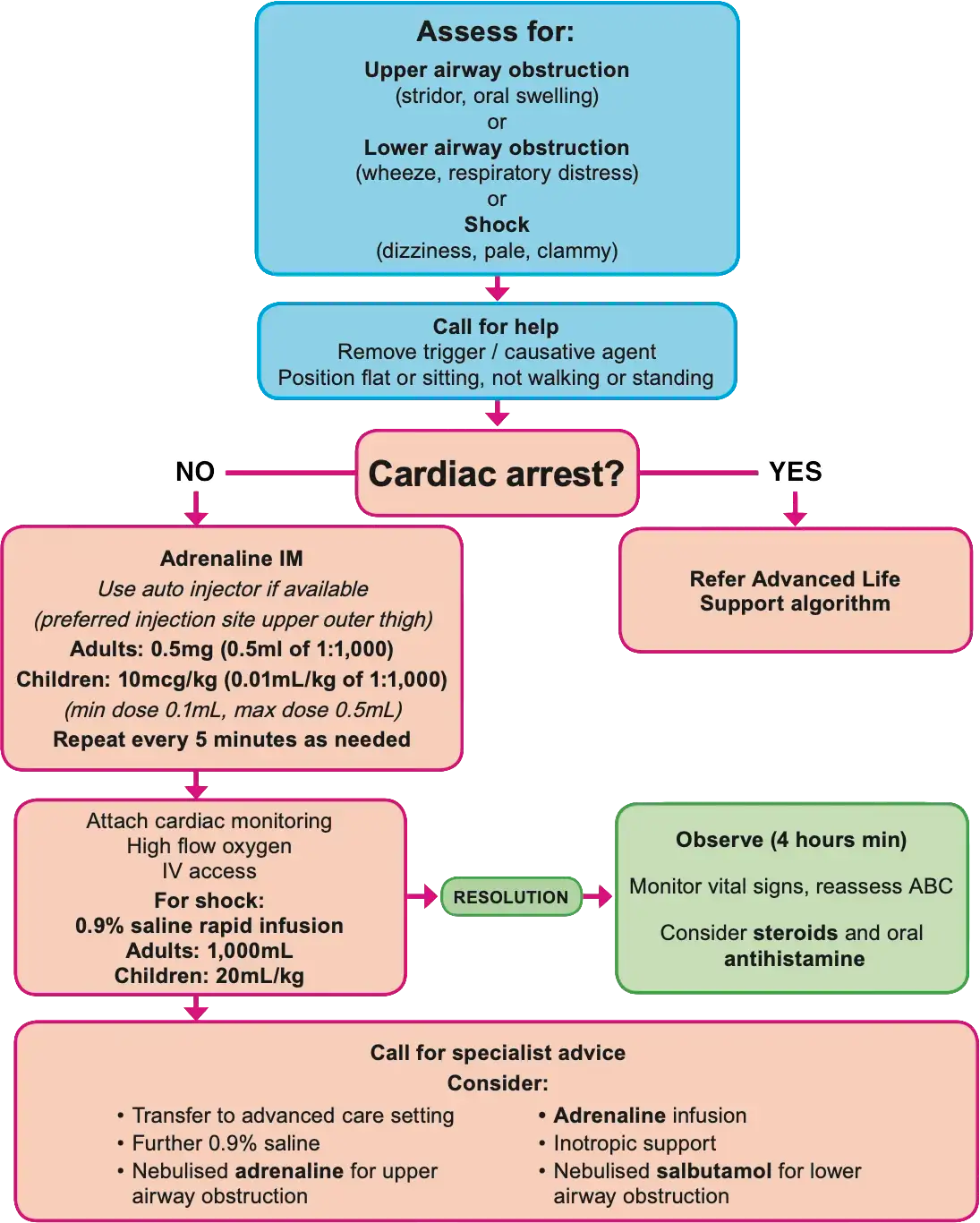

The Australian Resuscitation Council publishes a handy flowchart to guide your management. You should definitely practice it for the OSCE. The key points are…

- Call for help early

- Cease infusion of the offending agent

- Give intramuscular adrenaline 💉

- Rapidly infuse IV fluids

- Start CPR if they arrest

Cardiac Arrest 🫀

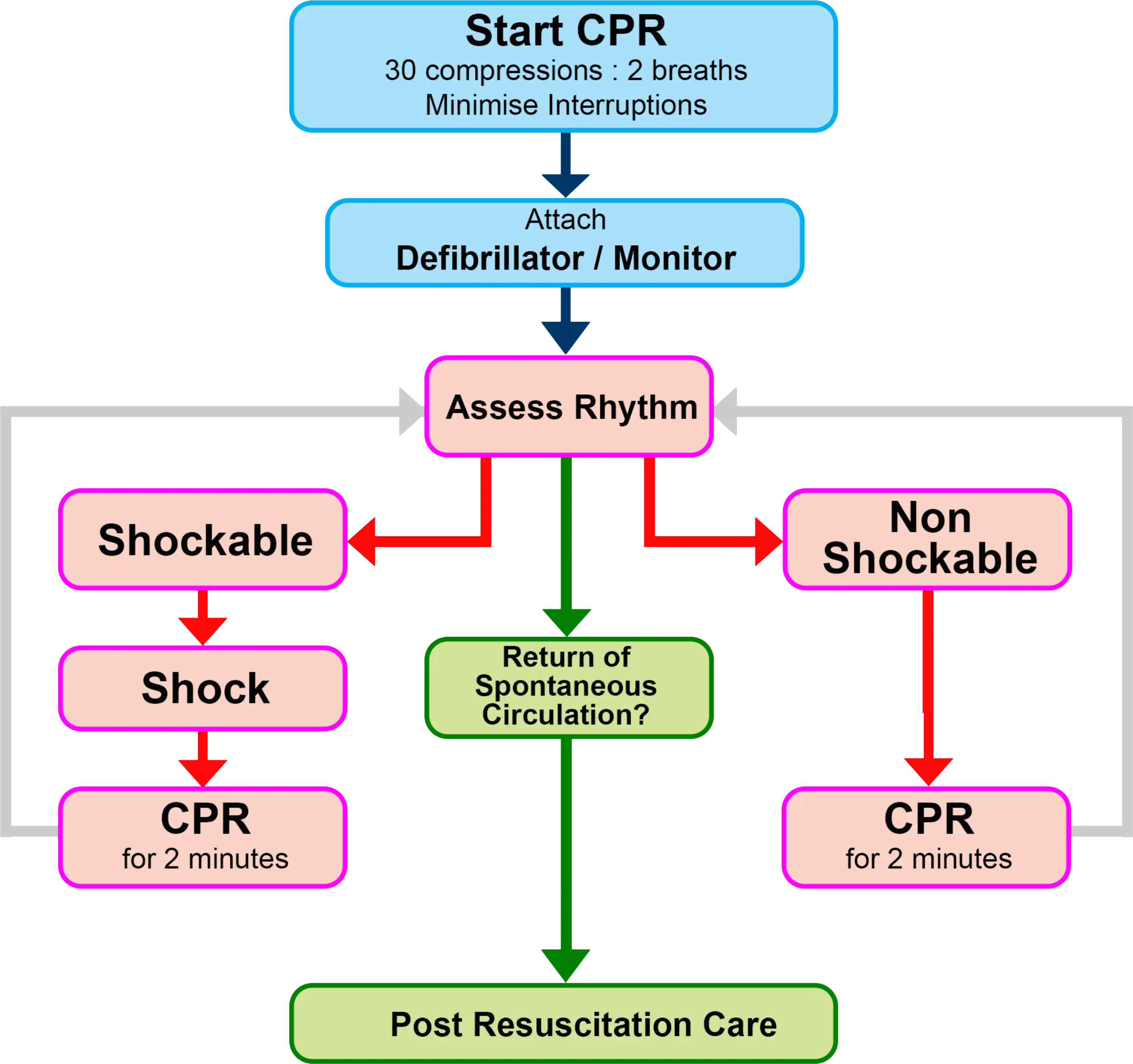

Arrest is rare in routine surgery, but you need to know it well for your exams. Call for help early and follow the Advanced Life Support algorithm…

Major Haemorrhage 🩸

Haemorrhage during surgery can be subtle but severe, especially in otherwise-healthy patients. Vigilance, early intervention and teamwork are vital.

Assessment

Signs that your patient is losing blood, in rough order of reliability are…

- You can see lots of blood

- Drains

- Surgical field

- The floor

- Tachycardia

- Tachypnoea

- Narrow pulse pressure

- Hypotension

- Oliguria

Remember that blood can also hide from you (and the surgeons) in the pelvis, long bones, mesothelial cavities, and the retroperitoneal space.

Management

The general aims of haemorrhage management are…

- Stop the bleeding

- Replace the missing volume

- Maintain normal blood composition

- Clotting factors

- Biochemistry

- Acid-base balance

When asked in an OSCE, you might suggest the following approach…

- Call for assistance

- Approach the patient in a DRS ABCDE structure

- There’s no use in transfusing a patient who cannot breathe

- Insert a wide-bore IV cannula in each arm

- Temporise the situation with volume expansion (crystalloid)

- Activate your hospital’s massive transfusion protocol

- Send blood for cross-matching

- Transfuse O-negative blood

- Consider giving platelets and fresh frozen plasma

CICO ⛔️

CICO (pronounced “kye-koh”) stands for “can’t intubate, can’t oxygenate”. This is one of the most feared anaesthetic emergencies because patients deteriorate quickly with little warning.

There are dozens of situation-specific guidelines for difficult airway management, and you don’t need to memorise them.

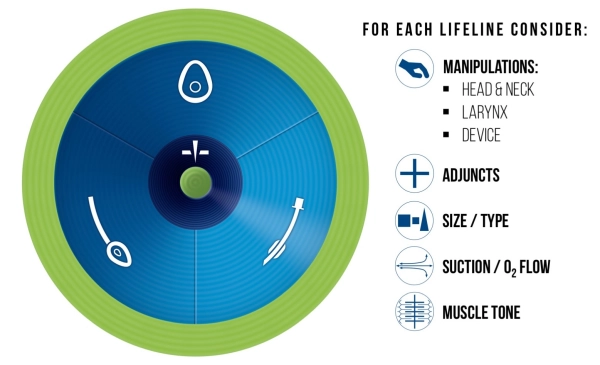

Instead, get familiar with the Vortex Approach…

Elaine Bromiley was a woman who tragically died from a poorly-managed CICO situation in 2005. Her death sparked an intense interest in airway emergencies that continues to shape the culture and practice of modern anaesthesia.

Everone who works in a hospital should watch this video by her surviving husband, Martin Bromiley:

Laryngospasm 🫁

Laryngospasm is a life-threatening contraction of the laryngeal muscles that causes complete (or near-complete) airway obstruction.

It is triggered by stimulation of the larynx (ahem, wiggling the LMA) without sufficient ablation of the airway reflexes. Children spasm far more than adults, especially when infected with a respiratory virus.

Tempting as it may be, never try to insert an endotracheal tube through closed vocal cords (they’re fragile). Instead:

- Deepen the anaesthetic

- Ventilate with 100% oxygen

- Turn up the pressure

- Paralyse the patient

Malignant Hyperthermia 🔥

Malignant hyperthermia (“MH” for short) is an inherited disorder of sarcoplasmic calcium release. Uncontrolled calcium release triggered by volatile anaesthetic agents and suxamethonium causes a hyper-metabolic state with a 100% mortality when left untreated.

MH is a once-in-a-career event and there is no expectation that junior doctors will know how to manage this crisis. You should, however, make a point of asking about it in every anaesthetic history.

Management

Cease administering the offending agent and start assessing the patient using an ABCDE approach. Surviving MH requires a tour de force in teamwork and crisis management, so call for help early.

Dantrolene is the only drug that works for MH. Administering it is the number one priority, followed by active cooling with ice and chilled IV fluids.